your inbox

Sign up for the High Line newsletter for the latest updates, stories, events & more.

Discovering New York City's Rich Railroad History at the Williamson Library

By Clay Grable | February 26, 2014

Michael Vitiello examines a book of old West Side Line (a.k.a. the High Line) advertisements in the Williamson Library.

On the wall of Michael Vitiello’s office, hidden in the upper levels of Grand Central Terminal, hangs a bronzed fedora. It belonged to Paul “Tick Tock” Kugler, the last clock master of Grand Central, who wore it to work there every day of his 47-year career. Michael, Grand Central’s supervisor of building maintenance, is the last person Tick Tock trained to service the station’s old self-winding clocks before he retired at age 70. The sole survivor of these “master clocks” also hangs in Michael’s office, a space that feels less like a workplace than a peek into an era that has slipped away.

After working in the terminal for 35 years, Michael is well on his way to becoming just as revered a figure as Tick Tock in the mythology of the world’s sixth-most-visited tourist site. With such a long and storied career, 60-year-old Michael couldn’t be called a “young whippersnapper” (his own words) by most standards. Improbably enough, he belongs to a group that considers him just that – the New York Railroad Enthusiasts.

The wall of Michael’s office, with Tick Tock’s bronzed fedora and the last master clock.

The New York Railroad Enthusiasts are exactly what they sound like. Founded in 1937, the NYRRE holds a monthly meeting to discuss rail travel, trains, and the history of that method of transportation. Despite being its vice president and a 14-year member, Michael is one of the more junior members of the group. The NYRRE’s current president, Allan Roberts, outranks Michael by roughly 26 years of membership. The organization holds its meetings in Grand Central’s Williamson Library, named for Fred Williamson, the president of the New York Central Railroad who gifted them the space.

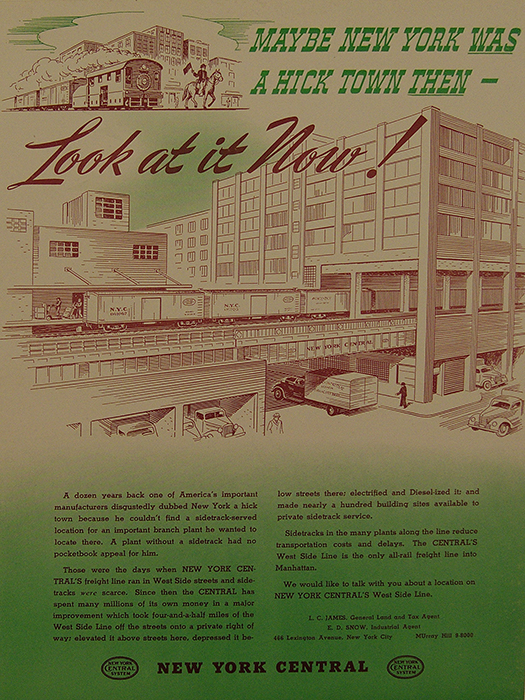

When we arranged to visit the library in January, our original purpose was to document a book of advertisements from the magazine The Westsider that depict the High Line in the 1930s through the 1960s, when it was still operational. As soon as we actually entered the Library, we were derailed, so to speak.

If Michael’s office is a glance into the past, the Williamson Library is a walk through Grand Central’s Main Concourse during rail travel’s heyday. A cross between a regular library, a museum, and a council chamber, the Williamson Library holds one of the largest collections of railroad records and memorabilia in the metropolitan area. It’s positively packed to the brim. Books line the walls where they’re not displaced by display cases full of models, pictures, hats, pins, and other souvenirs of time spent riding and working the rails. Opening the door, Michael becomes a kid in his very own candy shop. He immediately set about showing off and explaining his favorite artifacts, barely allowing us time to document everything he pointed out.

Michael identifies steam engines.

Among the artifacts in the library’s collection are an original – and very luxurious – chair and rug from the 20th Century Limited, a train Michael described as “the Concord of its time.” The rug is covered in what Michael calls “mummy” dust: dust that’s even older than the rug itself, having been passed around the station for decades before that specific train and its rugs were introduced. It’s easy to see how much Michael loves every inch of the room and its contents as he enthusiastically picks out various treasures for us to examine. A book used for showing English locomotives to American buyers, a photograph of Miss Empire State Express, a photograph of Ms. E.S.Exp. later in life holding the previous photo, and plenty of model engines make appearances. (His favorites are the streamlined, Art Deco models.) Michael is excited to retire, he claims, because then he’ll finally have time to read all of the library’s materials.

When we finally get to the book, titled New York Central’s West Side Line, New York: Advertisements Which Have Appeared in “The Westsider,” Michael’s tone changes from unrestrained enthusiasm to reverence. “We don’t know of any other book like this in existence,” Michael explained as he held the volume with the tips of his fingers. Regarding his delicate handling of the book, he said, “It’s like a baby.” We combed through it page by page, photographing every advertisement and marveling at the detail with which it depicted a style of life now thoroughly extinct. The West Side Cowboy, a favorite figure of ours, made appearances in a handful of the ads that emphasized the modernity of the High Line, which was then called the West Side Line. One ad depicts “Father Knickerbocker” standing over Manhattan, eating a train car on a fork while text explains that the West Side Line brings a whole carload of food into the city every minute. Art Deco sensibilities rule the day in the first pages of the book. As each advertisement advances chronologically to World War II, Uncle Sam makes a number of appearances, followed a few pages later by triumphant GIs returning home. The ads are colorful, intricate, and impressive. Before long, we realize that our humble hand-held camera isn’t enough to do the book justice. We’ll need to have it professionally scanned to make sure its contents are never lost to the ages.

Putting the book away, Michael relaxes and begins to share a bit about his own life. It turns out that railroads are in Michael’s blood : his family’s past, present and future entwine themselves with New York transportation. Michael’s uncle was a plumber in Grand Central, his grandfather was a blacksmith for New York City transit who forged steel parts for carriages, and his wife’s uncle worked for the transit authority. Michael won’t even collect social security when he retires; he’ll receive railroad retirement benefits instead. Railroads, the library, Grand Central – they’re all huge parts of Michael’s life. As we begin to leave, Michael confides that he’s worried about the collection’s uncertain future. “Not many places like the Williamson Library exist. Most places make you stand back; very few let you touch,” he says. And he doesn’t want a place like that to disappear.

The Williamson Library is a rare jewel, and not just because of its hands-on approach. It’s more than a repository for the history of New York’s various rail systems, it is itself a part of New York’s history. The library occupies its own chapter in the annals of one of the most important landmarks in the city, and keeps a fundamental part of our history alive. And although Michael didn’t mention this fact (seemingly the only one he didn’t), when Fred Williamson gifted the NYRRE their space in Grand Central, he did so in perpetuity. This deal should ensure that the Williamson Library continues to record our history even as the library itself gets written into it. With any luck, the Williamson Library will be around for as long as Grand Central will, which Michael and I agree should be for quite some time.

A model train spans the length of a display case in the Williamson Library.

High Line Visual Media Fellow Amelia Krales took this series of photographs in the Williamson Library.