your inbox

Sign up for the High Line newsletter for the latest updates, stories, events & more.

Behind the Bushes: The Queer History of the High Line

By High Line | June 24, 2021

In a lovely elegy for the “queer building” of 2 Columbus Circle, former New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp wrote about the role gay audiences play in historic preservation and reuse, and in the collective memory of a city:

The gay audience, excluded by society, has an organic relationship to artifacts that have been rejected by society’s taste-makers. Pluck a discarded ornament out of the town dump, take it home, polish it up and put it on a pedestal: It’s a way of refusing to abide by rules designed to shut you out. Somebody once loved that old lamp, that old building, that old street, that old neighborhood, that city that progress left behind.

We love that quote—because it describes the High Line exactly. If the High Line is a landmark today, much of the credit goes to the LGBTQ+ community, who encountered the structure during the 70s, 80s, and 90s, when it was hidden in plain sight. In those decades of disuse, the High Line was often the backdrop (and sometimes the stage) for gay countercultural social life, and the birth of the LGBTQ+ activist movement, in New York City.

That’s why Friends of the High Line wants to celebrate Pride Month with a look at “The Queer History of the High Line”—the history that helped save and shape the park.

The 70s and 80s

To most New Yorkers, coming upon the High Line before it was transformed into a park was a surprise—but to many LGBTQ+ people, it was known for decades, says our Co-Founder and Executive Director, Robert Hammond. That’s because it was next to clubs like the Tunnel, the Roxy, and Sound Factory, which were staples on the West Side of Manhattan. Hammond likes to joke about how many people say they discovered the High Line on their way to art galleries when they were really headed to gay clubs.

Hammond tells the story of one supporter: “When I asked him when he realized the High Line was even there, he said, When I leaned on it to vomit, coming out of the Roxy.”

From south to north, the High Line follows the path that the shifting hubs of gay social life in New York followed, starting in the West Village. In the 1970s, gay men priced out of that neighborhood started moving into Chelsea, where many opened shops along Eighth Avenue. Michael Shernoff, writing in LGNY, called these residents “pivotal in helping Chelsea become the vibrant and exciting neighborhood it is today.” Farther west, a different kind of neighborhood vibrancy and excitement quickly developed—a zone of gay sex clubs, offering sanctuary spaces and sexual freedom to gay men and transgender people. Photographer Katsu Naito documented many members of the transgender community in the book West Side Rendezvous, showcasing just how prevalent its members were around the Meatpacking District.

The High Line was a kind of informal gateway to this neighborhood, writes Friends of the High Line Co-Founder Joshua David: “To cross beneath it was to cross a line from the genteel blocks of the Chelsea Historic District to the raunchy, rough, industrial blocks of the Spike, the Eagle, Zone DK, the Mineshaft, and the Anvil.” These shrouded establishments were notoriously illicit; the Mineshaft, for example, located at 835 Washington Street (near the current Friends of the High Line office), was one of the most extreme. New York magazine published an eye-opening oral history of the club, and longtime gay nightlife chronicler Michael Musto described the scene in Paper magazine: “The ‘private membership club’… encouraged all manner of nudity and wild sex acts. I went once and remember that as you walked, the carpet squished.”

In this raunchy neighborhood, the High Line was itself a kind of secret club—an even more illicit and lawless space, where people often snuck up to have sex or do drugs.

Neighborhood activists

Despite these social and sexual sanctuaries, the neighborhood itself was not a safe space for gay men, transgender people, and others considered on the fringes of society, who were regularly targeted because of their orientation and attacked on their way to and from the clubs.

As part of the burgeoning community organizing movement offering services, support, advocacy, and fellowship for LGBTQ+ people, a group of activists set out to protect people on their way to and from the Meatpacking District parties. These included SMASH, the Society to Make America Safe for Homosexuals, which according to Shernoff organized “homopatrols” and confronted gangs of teenagers that targeted gay men.

These and other activists helped shape our city today. And our streets and landmarks carry some of their names (although not yet enough!)—like Sylvia Rivera Way, a street named for an often under-recognized leader of the gay rights movement. Rivera was part of the Stonewall Riots in 1969 and was an early and powerful activist for transgender people, especially homeless youth.

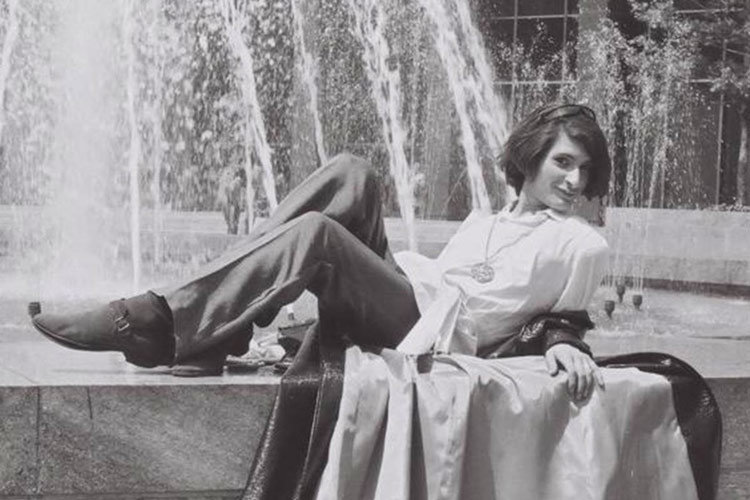

Sylvia RiveraPhoto by Kay Lahusen

Because so much of the neighborhood from those days is gone—the Christopher Street Piers long demolished, the Mineshaft and the Eagle replaced in a changed neighborhood (psst: you can still find the Eagle on West 28th)—the preservation of the memory is important. It’s even more vital because of the people we’ve lost: More than 100,000 New Yorkers have died of AIDS, a disproportionate amount from the LGBTQ+ community; the New York City AIDS Memorial, recently opened on 12th St. and Greenwich Ave., is a new pillar of memory for our collective loss.

The memorial marks the old site of St. Vincent’s Hospital, deemed “ground zero” for the city’s AIDS crisis for its role in the early days of the epidemic. The memorial calls us to remember the far-reaching impacts of the disease, compounded by stigma and the lack of legal rights for gay couples, many of whom were denied survivor benefits by the government, as well as families of victims. The new memorial is an important reminder of everything our city has lost—artists, activists, and loved ones—so that we don’t forget how New York has changed, in ways we often take for granted.

Queer life and historic preservation

In the work of inscribing our history onto our city, LGBTQ+ people have long played a vital role—that work Muschamp described in the Times of plucking “a discarded ornament out of the town dump” and putting it on a pedestal.

One of the early High Line supporters who most embodied this spirit was Florent Morellet. A pillar of the Meatpacking District, he ran his restaurant on Gansevoort St., Florent, for decades as a sanctuary for gay and transgender people. Opened in 1985, Florent was an exercise in preservation and love. Hammond described the restaurant: “You stepped through the meat scraps and fatty slime on the sidewalk to this 1940s diner that Florent had lovingly restored, with Formica tables, a red leather banquette that ran the length of the room, and framed maps of cities… It was democratic and welcoming—a great New York City scene.”

Morellet was a key figure in the High Line’s preservation, introducing Hammond and David to fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg and other early supporters of Friends of the High Line. Morellet also hosted fundraisers, including one where he dressed in a drag costume that was both Marie Antoinette—his long-running traditional anniversary outfit—and the High Line.

Morellet was fully committed to preservation; he was also co-founder, with Jo Hamilton, of Save Gansevoort Market, which won a historic landmark designation in 2003.

So many pillars of gay history in New York City helped shape the High Line. Former New York City Councilmember and Speaker Christine Quinn represented our district and was an early champion; watching her become the city’s first openly gay Council Speaker was a joyful moment. “I was so proud of Christine and so proud to live in New York City,” David remembers. Former council member and Speaker of the New York City Council, Corey Johnson, is equally supportive, along with the LGBTQ Caucus of the City Council. Other gay government leaders who have played or continue to play roles in helping the High Line include former New York State Senator Tom Duane and current New York State Senator Brad Hoylman.

But Pride Month isn’t just about the luminaries of history—it’s about all of us who make and shape our city every day. Many of the most influential activists and representatives of the gay rights movement have worked behind the scenes, and we too rarely recognize the work of those who start from difficult places. As the High Line continues our work as not just a landmark but a living part of a changing city, we hope to serve as a safe, open, and welcoming public space where everyone can see themselves reflected.