your inbox

Sign up for the High Line newsletter for the latest updates, stories, events & more.

Ruth Ewan’s Silent Agitator and the Industrial Workers of the World

By High Line Art | August 30, 2019

Ralph Chaplin’s stickerette for the IWWPhoto by Courtesy of Catherine Tedford, Richard F. Brush Art Gallery, St. Lawrence University

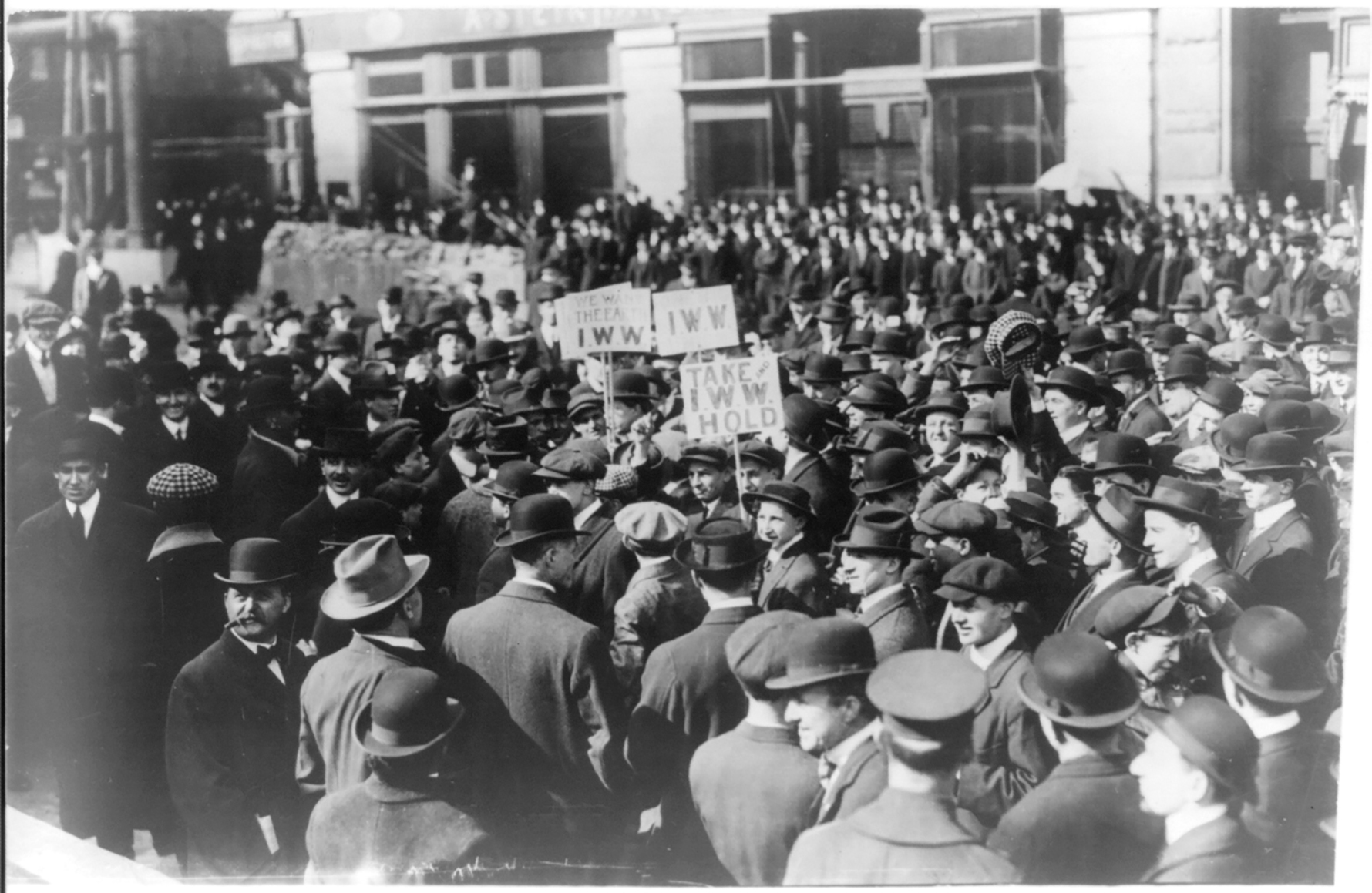

Industrial Works of the World demonstrate in New York City, 1914This year on the High Line, visitors can stop to check the time at Ruth Ewan’s installation Silent Agitator. This work is monumental-scale clock on the park at 24th Street, also visible from street level. The clock is based on an illustration originally produced for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union by the North American writer and labor activist Ralph Chaplin. It reads “What time is it? Time to organize!”

The illustration was one of many images that appeared on “stickerettes,” known as “silent agitators,” millions of which were printed in red and black on gummed paper and distributed by union members traveling from job to job. The stickers were advertised through publications such as Solidarity and the union’s newspaper Industrial Worker, and through events such as national “Stickerette Day” on April 29, 1917, and May Day of the same year.

A diverse group of socialists, anarchists, labor activists, schoolteachers, and immigrants founded the IWW in June 1905 in Chicago, in response to the fractured unionizing of the day and the need for solid organization around workers’ rights. Their main organizing principle is the concept of One Big Union—or a unified conglomerate of workers, regardless of trade or experience. This type of organizing is called Industrial Organization.

An IWW demonstration in New York City in 1914

They believed that craft unionization, or smaller factions separated by workers’ tools (i.e. plasterers with plasterers, painters with painters), failed to successfully organize the working class against the exploiters of their labor because of its narrow approaches. Instead, the IWW, or the Wobblies, included all workers, across genders, race, and craft into one union. The Wobblies were also one of the only unions to welcome immigrants. Famous immigrant organizers like Carlo Tresca, Joe Hill, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, were all Wobblies. The IWW motto was “an injury to one is an injury to all.”

The Wobblies based many of their union principles in Marxism, socialism, and anarchism, specifically one of the most important principle of these three ideologies: direct action. In practice, direct action means strikes, boycotts, soapboxing, and the distribution of media, such as newsletters and stickerettes.

Cultural artifacts from the beginnings of the IWW speak to the importance of flyering, postering, and distribution of materials in order to garner support and followers for the movement. Stickerettes were important illustrations that were easily understood across languages and cognitive abilities and swiftly spread from town to town, county to county, and across state lines. Famous images of this era include the Black Sabo cat with its arched back, and the wooden clog, known as Sabot, from which the word “sabotage” derives. The term references either a) the way the clumsy shoe impeded workers’ ability to move into action, or b) disgruntled workers who threw their wooden clogs into their work machines to damage the cogs and wheels.

A pair of sabotsPhoto by Sunny Ripert

Ralph Chaplin, one of the IWW founders, in addition to his illustration work, wrote many of the galvanizing songs for the union movement. Chapman composed the famous “Solidarity Forever” for the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek coal miner strike of 1912 in Kanawha County, West Virginia, excerpted here:

All the world that’s owned by idle drones is ours and ours alone.

We have laid the wide foundations; built it skyward stone by stone.

It is ours, not to slave in, but to master and to own.

While the union makes us strong.

Chorus:

Solidarity forever,

Solidarity forever,

Solidarity forever,

For the union makes us strong.

Lucy Parsons, activist, anarchist, and IWW member

IWW co-founder and anarchist Lucy Parsons, a trailblazer then and now, wrote this prescient piece for the IWW newsletter in 1912:

“A reduction of the working time is the most just and practical palliative that can be injected into the issue between labor and capital. In fact, while it seems to be a palliative on the face of it, it is in reality not a palliative at all, but a revolutionary measure, because time is the greatest factor in our existence.

The worldwide unrest among the wage class is the most hopeful sign of the times. Labor is learning that its most powerful and effective weapon is in its muscles and its brains. Let it withdraw these and the capitalist system is paralyzed. What labor wants is land for the landless, produce to the producer, tools to the toiler and death to wage-slavery.”

(You can see Lucy commemorated in one of the posters in our High Line Art and High Line Network collaboration New Monument for New Cities.)

Schisms amongst the IWW in the 1920s and anti-union legislation led by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and President Truman, such as the passing of the Taft-Hartley Act, restricted union activities and caused membership to decline; but the Wobblies were rejuvenated in the 1960s as they fought against the Vietnam War and for Black American civil rights. In the 1970s they returned to their workforce organizing, spreading to the entertainment industry, incarcerated workers, and student college organizations. Their fights included calls for medical and dental insurance, resistance to gentrification, contract and booking rights for musicians, free speech, and health and safety guarantees.

Well over one hundred years later, workers are still battling for their time and labor rights, including all of the above. And as industry declines worldwide and gives way to automation and the information economy, the structural relationship between the trifecta of labor, wage, and capitalism is shifting toward an unknown future. Many people work several jobs, and well over forty hours a week, without health insurance or job security. It’s estimated that nearly 40% employees in the United States work 45 or more hours each week, and about 20% clock in at 60 hours or more. Furthermore, the constant connection to the internet allows work to seep into every corner of our lives.

Ewan’s clock enters in this uncertain moment in labor history. Silent Agitator acknowledges the round-the-clock organizing work of the IWW, and nods to the ubiquity of the clock in labor struggles: the clocking in and out that marked the backbreaking, upwards of 100-hour-long work weeks, and the long battle for the five-day work week and eight-hour day, started by the Ford Motor Company in 1925 and placed into law with the (amended) Fair Labor Standards Act in 1940.

‘Back to the Fields’, 2015/16 French Revolutionary, Republican Calendar Installation view ‘Incerteza Viva’; 32nd Bienal de Sao PauloPhoto by Leo Eloy/ Estúdio Garagem

Silent Agitator isn’t the first project of Ewan’s that explores various measures of time. In 2016, she converted an unused field in Cambridge, England into a clock timed to the blooming of native flora in an installation called Another Time. A year prior, she installed an intricate and rigorous multi-part work called Back to Fields at Camden Arts Centre in London, which enacted the Republican calendar created by Charles-Gilbert Romme that was in use for twelve years during the French Revolution from 1793 to 1805 and reintroduced for 12 days during French anarchist revolution the Paris Commune in 1871. Romme structured this calendar on the ideals of the rebellion—eschewal all religious and political associations in favor of the cycles relevant to the rural proletariat. He named the months, then, for the changing seasons and weather.

Seen together, these three works—Silent Agitator, Back to the Fields, and Another Time—represent an interest in how politics and economies skew our a natural relationship to time. They remind us that we can mark its passage in other ways, such as the movements of our days, the rhythms of plants, or the coming and going of spring, summer, winter, and fall.

Like Ewan’s other works, Silent Agitator asks visitors to stop on their walk along the conduit of the High Line to reflect on their relationship to time and labor. By bringing the clock outside, Ewan speaks to the private vs. public separation of space and time we experience in wage-labor capitalism, and a possible future where people gather together for the reclamation of their precious time.

You can see Ruth Ewan’s Silent Agitator on the High Line at 24th Street now through March 2020.